Please forward and share this ezine with others. Thank you.

Contents

- Writer’s Corner

- Blessed Unbeliever

- This month’s story: Plumbers and Electricians

- This month’s puzzler: Who done it?

- WINGSPREAD Ezine subscription information

- Wisdom

Writer’s Corner

Dedicated to people who love words. Words are miracles that brand humans as sentient creatures, creative, inventive, exploring. Taste the words as they roll around on your tongue; let them fill you with a sense of wonder.

NEW BOOK! I have begun assembling a new book of stories and essays gleaned from the last ten years of my blogs. Maybe I’ll group these under the sections: Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Spoiler alert: I’m in the “Winter” phase now, and looking back to those other seasons. I’ll keep you posted.

Why it’s important to write

Want to browse archived WINGSPREAD stories? Click here, then click under “archives” https://jimhurd.com/ These stories include memoirs, stories about bush flying, personal essays and other topics. They’re searchable for key words.

Here are a few examples:

The joys of my annual physical exam: https://jimhurd.com/2024/10/25/the-annual-physical/

Why did it take so long to discover that I’m not weird? https://jimhurd.com/2024/02/06/a-letter-to-my-fourteen-year-old-self-you-are-not-weird/

Writer’s tip: Transgress. You seize the reader’s interest if you write something unexpected. Examples: “I’ve given up on Jesus.” “Morality is so 19th century.” Of course, your piece will sort out these shocking statements and explain what you mean. But use counterintuitive and contrary statements: contradictions, hyperbole, even forbidden words (used carefully). The object? Transgressing grabs the reader’s attention.

Words and metaphors

“a unicorn of a girl” (unique type)

“he shat his pants” (quite vivid)

haplotype (a sequence of polymorphic genes that tend to be inherited together). This is the way Ancestry.com discovers your ancestry.

Digital resources:

I still own my Strunk and White, Elements of Style, but you can ask AI (Artificial Intelligence) anything. Try typing into your browser: “chatgpt.” For instance: “What’s the difference between insure and ensure?” “When must you use a comma before a conjunction?” or “Please critique the attached story and give me suggestions on how to improve it.” What I do not do is ask AI to write the story for me.

Word of the month. FAIN (obsolescent): Gladly, willingly

Task for you: Write about how joyful you are without saying how joyful you are. (That is, show; don’t tell.)

BLESSED UNBELIEVER novel

Available in paper or Kindle version at Wipf and Stock Publishers, Amazon https://a.co/d/9su5F3o or wherever good books are sold.

Hashtags for the book: #california #author #christianwriter #babyloss #southerncalifornia #oc #planes #socal #aviationdaily #humanist #pilotlife #blessedunbeliever #religion #travel #christianauthor #aviationgeek #orangecounty #godless

New story: ”Plumbers and Electricians”

Retirement is deceptive. You’re lulled into thinking that things will pretty much go on as they always have. They usually do. But then, life happens.

I’m working in my college office when the phone rings. “Jim, I don’t know what to do. I’m just sitting here on the sofa sewing and three times I’ve felt faint—like I’m about to pass out.”

My mind races. Is this just in Barbara’s head? In the past, I’ve joked with her that I’ve decided on her epitaph: “I told you I was sick!” But what if something’s really going on? She’s never complained about feeling faint before.

“How often is this happening to you?

“About every half hour or so. Oh! I feel like I’m fainting now!”

“Okay—I’m calling 911 and I’ll come home as soon as I can.”

I call 911, run out to my car, and drive home, praying as I go. When people ask me how prayer works, I always have a ready answer: “I don’t know. But the Bible tells us to pray, and Jesus prayed, so I pray.” . . . To read more, click here: https://tinyurl.com/4tshbrbb

Please “rate” the story and “share” it with others. Thanks.

You can also access my articles on Substack: Plumbers and Electricians – by James P Hurd

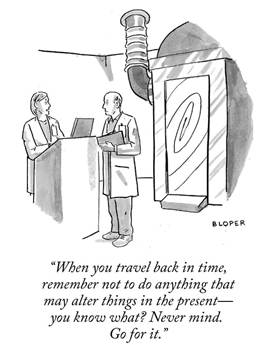

This month’s puzzler. thanks to Car Talk Archives

This one is clever. You have to look closely at the following paragraph. You should actually not read it; you should have someone else read it to you to get the full experience. But you can read it if you have to.

Here it is.

“This paragraph is odd. What is its oddity? You may not find it at first, but this paragraph is not normal. What is wrong? It’s just a small thing, but an oddity that stands out. If you find it, what is it? You must know your days will not go on until you find out what is odd. You will pull your hair out. Your insomnia will push you until your poor brain finally short circuits trying to find an oddity in this paragraph. Good luck.”

So what is it?

Remember, you have to examine the paragraph really well.

Good luck.

(Answer will appear in next month’s WINGSPREAD newsletter.)

Answer to last month’s puzzler:

So, a night watchman hears a person scream “No, Frank!” Then a gunshot. He enters the room and sees a minister, a plumber and a doctor. But how does he know that it was the minister that pulled the trigger?

Easy.

The doctor and the plumber are women. So he made the likely guess that none of the women were named Frank.

Subscribe free to this Ezine

Click here https://jimhurd.com/home/ to subscribe to this WINGSPREAD ezine, sent direct to your email inbox, every month. You will receive a free article for subscribing. Please share this URL with interested friends, “like” it on Facebook, retweet on Twitter, etc.

If you wish to unsubscribe from this Wingspread Ezine, send an email to hurdjames1941@gmail.com and put in the subject line: “unsubscribe.” (I won’t feel bad, promise!) Thanks.

Wisdom

Q. How do you keep your car from being stolen?

A. Buy a standard shift model

Q. How do you send a message in code?

A. Write in cursive

“Critical thinking without hope is cynicism. Hope without critical thinking is naiveté. Maria Popova

Here are some irreverent trivia questions about college football:

What does the average Alabama football player get on his SATs?

Drool.

How many Michigan State freshmen football players does it take to change a light bulb?

None. That’s a sophomore course.

How did the Auburn football player die from drinking milk?

The cow fell on him.

Two Texas A&M football players were walking in the woods. One of them said, ” Look, a dead bird.”

The other looked up in the sky and said, “Where?”

What do you say to a Florida State University football player dressed in a three-piece suit?

“Will the defendant please rise.”

How can you tell if a Clemson football player has a girlfriend?

There’s tobacco juice on both sides of the pickup truck.

What do you get when you put 32 Kentucky cheerleaders in one room?

A full set of teeth.

University of Michigan Coach Jim Harbaugh is only going to dress half of his players for the game this week. The other half will have to dress themselves.

How is the Kansas football team like an opossum?

They play dead at home and get killed on the road

How do you get a former University of Miami football player off your porch?

Pay him for the pizza.

On the Act of Writing:

- “The first draft is just telling yourself the story.” – Terry Pratchett

- “If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time—or the tools—to write.”

– Stephen King - “Writing is a way of tasting life twice.” – Anaïs Nin

- “Write what you know.” – Mark Twain

- “Write the book you want to read.” – Toni Morrison

- “Words are our most inexhaustible source of magic.” – J.K. Rowling

- “Writing is a dog’s life, but the only life for me.” – Gustave Flaubert

Why some people don’t like Daylight Savings Time

Wisdom and Philosophy

- “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”—Franklin D. Roosevelt

- “Be yourself―everyone else is already taken.”—Oscar Wilde

- “The mind is everything. What you think you become.”—Buddha

- “The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.”—Lao Tzu

- “In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: it goes on.”

—Robert Frost - “The unexamined life is not worth living.”—Socrates