Spreading your wings in a perplexing world

August 2023 James P. Hurd

Please forward and share this E-zine with others. Thank you.

Contents

- Blessed Unbeliever now available in Australia!

- Writer’s Corner

- New story

- This month’s puzzler

- Wingspread Ezine subscription information

- Wisdom

BLESSED UNBELIEVER novel

I am thrilled that Koorong, largest Christian book publisher in Australia, will distribute Blessed Unbeliever.

Blessed Unbeliever (paper or Kindle version) can be found at Wipf and Stock Publishers, Amazon https://a.co/d/9su5F3o or wherever good books are sold.

Writer’s Corner

Tip for writers: Always have at least two projects going. That way, if you get stumped or bored, you can switch to your other project awhile.

Word of the Month: LAYOUT: This is everything that is done after your manuscript is finished, revised and edited and before it is published. Things like type font, paragraphing, margins, headings, front and back matter, cover design, back cover endorsements, chapter numbering and headings, and a host of other decisions. Really—it’s a big deal—you might wish to get it done professionally.

Book of the month: TRINITY, Leon Uris. 1976. 749 pages. A sloggy but powerful historical novel about the English/Irish, Protestant/Catholic, North/South conflicts. Requires patience, but it’s worth it. Colonization, famine, war. The tragedy of Ireland.

Question for you: If you were stranded on a desert island and could have only five books, which would you have? I’ll list these books in next month’s WINGSPREAD.

New story: Searching for Mr. Texas

You can’t tell Texas is coming but the mountains and mesas of New Mexico gradually morph into undulating plains as we enter the Panhandle. When we pass the vast ranches and the horse-headed oil donkeys, I wonder, Does the Panhandle produce anything besides oil and cattle? Bold, proud, independent, self-made Texas. She doesn’t even seem to notice we’ve come.

We finally arrive at Uncle John’s ranch, drive through the gate with the cast-iron brand “Derrick Ranch” overhead and park in front of the brick rambler. . . .

To read more, click here: https://jimhurd.com/2023/07/28/searching-for-mr-texas/ Leave a comment on the website and share with others. Thanks.

This month’s puzzler

(Adapted from Car Talk Puzzler archives)

A very long time ago, back in the day, I was test driving a BMW with a five-speed manual transmission. I had my son Andrew along with me at the time. He was about 12 years old or so. We were heading to Toys-R-Us, or something. We are driving along on the highway.

So there we are, and he looks over at the speedometer and says, “Gee Daddy, will this thing really go 160 miles per hour?” He always asks this question when we are test driving a car.

I looked down at the speedometer and the dashboard and then I said, “No, it won’t.”

A week later, he and I were again test driving a car. And this time, we were driving in a Mustang with a five-speed manual transmission. And like always, he looks over and says, “Gee Daddy, will this car do 160? Because that’s what the speedometer says?”

So, I look down at the dashboard and then I say, “Yes, this one will.”

So, the puzzler is, how did I know that?

(Answer will appear in next month’s WINGSPREAD newsletter.)

Answer to last month’s puzzler:

Recall: It was a beautiful sunny summer afternoon in 1958. And I was driving my new car. I stopped at a stoplight, and a pedestrian noticed I had stopped.

Then he stepped off the sidewalk and walked right into the front right fender of my car.

What happened here?

Well, it was 1958. And the car I was driving was a brand new VW Bug. And as we all know, the VW Bugs had the engine in the back, and the trunk space in the front.

And the pedestrian was blind. So, he was used to hearing the engine in the front of the car. He heard mine, assumed the car was a few feet back from where it was, and he walked right into my car.

This would not happen these days, for sure.

Subscribe free to this Ezine

Click here https://jimhurd.com/home/ to subscribe to this WINGSPREAD Ezine, sent direct to your email inbox, every month. You will receive a free article for subscribing. Please share this URL with interested friends, “like” it on Facebook, retweet on Twitter, etc.

If you wish to unsubscribe from this Wingspread Ezine, send an email to hurd@usfamily.net and put in the subject line: “unsubscribe.” (I won’t feel bad, promise!) Thanks.

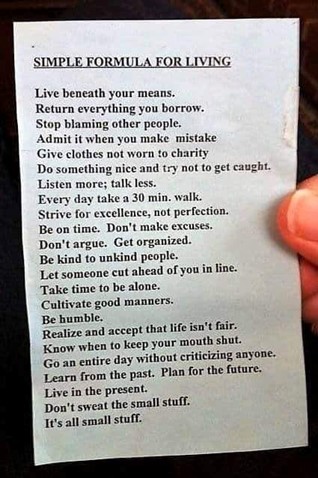

Wisdom

Relationships move at the speed of trust.

Where do bad rainbows go?

Prism. It’s a light sentence, and gives them time to reflect.

(This story is enlightening.)

Minnesota Bible verses:

- It is what it is.

- What goes around comes around.

- It’s all good.

- Whatever

Things I learned getting old . . .

1. When one door closes and another door opens, you are probably in prison.

2. To me, “drink responsibly” means don’t spill it.

3. Age 60 might be the new 40, but 9:00 pm is the new midnight.

4. It’s the start of a brand new day, and I’m off like a herd of turtles.

5. The older I get, the earlier it gets late.

6. When I say, “The other day,” I could be referring to any time between yesterday and 15 years ago.

7. I remember being able to get up without making sound effects.

8. I had my patience tested. I’m negative.

9. Remember, if you lose a sock in the dryer, it comes back as a Tupperware lid that doesn’t fit any of your containers.

10. If you’re sitting in public and a stranger takes the seat next to you, just stare straight ahead and say, “Did you bring the money?”

11. When you ask me what I am doing today, and I say “nothing,” it does not mean I am free. It means I am doing nothing and wish to continue doing it.

12. I finally got eight hours of sleep. It took me three days, but whatever.

13. I run like the winded.

14. I hate when a couple argues in public, and I missed the beginning and don’t know whose side I’m on.

15. When someone asks what I did over the weekend, I squint and ask, “Why, what did you hear?”

16. When you do squats, are your knees supposed to sound like a goat chewing on an aluminum can stuffed with celery?

17. I don’t mean to interrupt people. I just randomly remember things and get really excited.

18. When I ask for directions, please don’t use words like “east.”

19. Don’t bother walking a mile in my shoes. That would be boring. Spend 30 seconds in my head. That’ll freak you right out.

20. Sometimes, someone unexpected comes into your life out of nowhere, makes your heart race, and changes you forever. We call those people cops.

21. My luck is like a bald guy who just won a comb.”

-source unknown.