Spreading wings in a perplexing world

October, 2025 James P. Hurd

Please forward and share this ezine with others. Thank you.

Contents

- Writer’s Corner

- Blessed Unbeliever

- This month’s story: “The Returning”

- This month’s puzzler:

- WINGSPREAD Ezine subscription information

- Wisdom

Writer’s Corner

Dedicated to people who love words. Words are miracles that brand humans as sentient creatures―creative, inventive, exploring. Taste the words as they roll around on your tongue; let them fill you with wonder.

Want to browse archived WINGSPREAD stories? Click here, then click under “archives” https://jimhurd.com/ These stories include memoirs, stories about bush flying, personal essays and other topics.

Here are a few examples:

“Why do I Make Stupid Mistakes?”

https://tinyurl.com/4b36sest

“A Blessed Death” https://jimhurd.com/2025/01/

Writer’s tip: If you’ve seen a metaphor used before, don’t use it. So many metaphors are hackneyed and trite (a purring engine, flat as a pancake, as bright as the sun) Try to think of fresh metaphors.

Word of the month: A “contronym” is a word with two opposite meanings. For example:CLEAVE – to split apart (“Cleave the log in two”) -or- to cling to (“Cleave to your principles”).

Task for you: Incorporate two new words into the next paragraph you write. You may even, like Shakespeare, make up your own words. Try turning a noun into a verb (“The baby aped her mother’s motions perfectly.”)

Book of the month: Christian Reflections. C.S. Lewis (Walter Hooper, editor). 1967. Nerd alert—sometimes Lewis is hard to read. And yet here he reflects on important issues: Unanswered prayer, ethics, Christianity and culture. Ironic that even right-wing Christians have “adopted” this pipe-smoking, bourbon-drinking Oxford don who accepts evolution and speculates about purgatory! However, he lends his great mind to powerful Christian apologetics.

BLESSED UNBELIEVER novel

Available in paper or Kindle version at Wipf and Stock Publishers, Amazon https://a.co/d/9su5F3o or wherever good books are sold.

New story: “The Returning”

Fifty-four years ago I traveled from Venezuela to Pennsylvania for our wedding. Now I’m tearing up entering Pennsylvania for the first time without Barbara. I learned to see this world through her eyes―now I love the place even more than she did.

This year spring has come early to Lancaster County—green meadows of alfalfa, new-leaved trees, gardens of tulips, daffodils and phlox, the faint smell of spread manure. We pass eternal stone barns with their earth bridges rising to the second level. We hear the clip-clop of passing grey and black buggies.

We find the Willow Street Mennonite Church is thriving—lots of young families and children with many of Barbara’s relatives sprinkled in. A good Easter service. The promise of new life even as we memorialize its ending. I hear the “Lancaster lilt”—”youse staying for dinner? . . . it spited me . . . outen the light . . . there’s more pie back . . . baby’s all cried up; maybe she needs drying . . .”

To read more, click here: https://jimhurd.com/2025/10/01/the-returning/

Leave a comment on the website, subscribe and share with others. Thanks.

You can also access this and other recent articles on Substack: https://jameshurd.substack.com/p/the-returning

This month’s puzzler (thanks to Car Talk Archives)

An off-duty policeman is working as a night watchman in an office building.

He’s doing his nightly rounds, and he comes to a closed door. Behind the door, he hears voices.

He hears people talking, and an argument seems to be taking place. Raised voices, and yelling. Then he hears one of them say, “No, Frank! No, don’t do it. You’ll regret it.”

And then he hears what sounds like gun shots. Bang, bang, bang.

He burst through the door. What does he see? A dead man on the floor, and the proverbial smoking gun.

Now, in the room there are three living people. A minister, a doctor and a plumber.

He walks over to the minister and says, “You’re under arrest. You have the right to remain silent.”

How does he know that it was the minister that pulled the trigger?

Good luck.

(Answer will appear in next month’s WINGSPREAD newsletter.)

Answer to last month’s puzzler:

With the velociraptors pursuing you on Isla Nublar, your life depends on taking the correct fork in the road. You meet two guys—one always lies; the other always tells the truth. You get only one question. So what would the one question be to make sure you could get to the dock?

Here it is.

I would look at one of the guys and say, “If I were to ask the other guy which road takes me to the dock, what would he say?”

Here’s why.

If you ask the truth teller, he is going to say, “The liar is going to tell you to take this road.” And that would be the wrong road, because he’s a liar.

And if you ask the liar, he is going to point to the same road, because he has to lie about what the truth teller will say.

So there ya have it.

Subscribe free to this Ezine

Click here https://jimhurd.com/home/ to subscribe to this WINGSPREAD ezine, sent direct to your email inbox, every month. You will receive a free article for subscribing. Please share this URL with interested friends, “like” it on Facebook, retweet on Twitter, etc.

If you wish to unsubscribe from this Wingspread Ezine, send an email to hurdjames1941@gmail.com and put in the subject line: “unsubscribe.” (I won’t feel bad, promise!) Thanks.

Wisdom

- Pre- means before, and post- means after. Using both at the same time would be preposterous.

- Through prayer the Christ within us opens our eyes to the Christ among us.

Henri Nouwen

Depending on each other: Every morning for years, at about 11:30, Yolanda, the telephone operator in a small Sierra-Nevada town, received a call from “James” asking the exact time. One day the operator summed up nerve enough to ask James why the regularity.

“I’m foreman of the local sawmill,” he explained. “Every day, I have to blow the whistle at noon, so I call you to get the exact time.” Yolanda giggled, “That’s interesting, All this time, we’ve been setting our clock by your whistle.”

Obsolete Insults & Colorful Terms

- caitiff – wretched, despicable person

- knave – dishonest man

- varlet – rogue or rascal

- coxcomb – vain, conceited man

- scullion – kitchen servant (used insultingly)

- slubberdegullion – slob, slovenly person

- looby – awkward, clumsy fellow

Ode to the Married Man

To keep your marriage brimming

with love in the loving cup

whenever you’re wrong admit it

whenever you’re right, shut up.

Ogden Nash

Learning how to order coffee

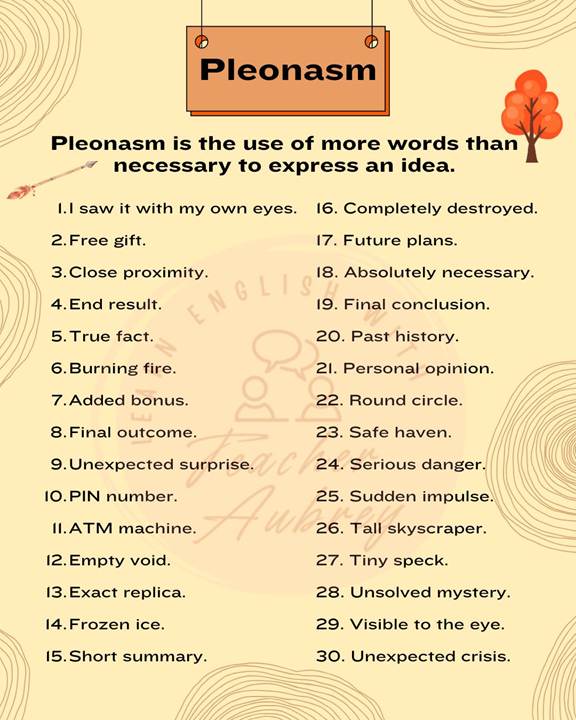

This list will help you tighten your writing―eliminate unnecessary words. My personal opinion is that this list is absolutely necessary―it’s a true fact.

Advice for parents